Articles Archive

Posts

- "I am the mother of the wicked (1)

- 20.07.09 Blood Donation Drive at Bukit Jambul (1)

- 2008 Photos (1)

- A Nice Article about Love-by Swami Vivekananda (1)

- as I am the mother of the virtuous. (1)

- Biography of swami vivekananda - Meditation and Psychic Powers (1)

- Can Be a Star (1)

- Cheque presentation for the purchase of Urvan (microbus)to The Ramakrishna Ashrama Penang by YB Jagdeep Singh Deo on 22.9.2010. (1)

- Complete works of swami vivekananda - Deccan Herald » City Today - Deccan Herald (1)

- Complete works of vivekananda - Origins of Yoga (1)

- DIVINE MOTHER'S BELOVED CHILD (1)

- Enlightenment and Ramakrishna 2 (1)

- Free Medical Camp Photos - 18/7/2010 (1)

- Healing Through Faith and Love - A Case Study of Sri Ramakrishna (1)

- How to deal with the wicked - Paramahamsa answers (1)

- Kind Word for Sri Ramakrishna (1)

- Kundalini Kriyas (1)

- Life of swami vivekananda - A 13-foot bronze statue of Swami Vivekananda (1)

- My dear brother (1)

- Osho on Ramakrishna Enlightenment (1)

- Pavagada - Home (1)

- Quotes of Sri Ramakrishna (1)

- Ramakrishna - Tribute to Jesus Christ (1)

- Ramakrishna Ashram Penang (1)

- Ramakrishna biography - My Gospel masterpiece hanging on Archbishop’s wall - Belfast Telegraph (1)

- Ramakrishna kathamrita - by Swami Vivekananda (1)

- Ramakrishna math - Swami Vivekananda - Concept of Religion as the Unfoldment of the Inherent Divinity in Man (1)

- Ramakrishna math - Swami Vivekananda — Soulful Tributes (1)

- Ramakrishna mission new york - Astrological Guidance And Destiny (1)

- Ramakrishna mission new york - In Hyderabad Today - Hindu (1)

- Ramakrishna Paramahamsa (2)

- Ramakrishna paramahamsa - Gospel Music Hall of Fame reveals latest class - Nashville Tennessean (1)

- Ramakrishna paramahamsa - Sri RamaKrishna Mission Vidyalaya - Wikipedia (1)

- Ramakrishna pictures - Hindu Poet - Kamalakanta (1)

- Ramakrishna vivekananda center - Sri Ramakrishna (1)

- Ramakrishna vivekananda info - How To Overcome Fear Using Power Of Love (1)

- Ramkrishna mission - Gospel Hankie Card † Pocket Witness † Wordless Ties (1)

- Read Swami Vivekananda (1)

- Real Guru - Swami Vivekananda (1)

- same chapter. - Minneapolis Star Tribune (1)

- same gospel (1)

- Shaktipat (1)

- Siddhis (1)

- Spirituality of Sri Ramakrishna (1)

- Sri ramakrishna paramahamsa - Pancikaranam - 9 (1)

- Sri ramakrishna paramhansa - Inspiration of Sri Ramakrishna (1)

- Sri Ramakrishna Story (1)

- Sri Sarada Devi (1)

- Sri Sarada Devi is the first disciple of Ramakrishna (1)

- Swami Abhedananda (1866 - 1939) (1)

- Swami Adbhutananda (d. 1920) (1)

- Swami Advaitananda (1828 - 1909) (1)

- Swami Akhandananda (1864 - 1937) (1)

- Swami Brahmananda (1863 - 1922) (1)

- Swami Niranjananda (d. 1904) (2)

- Swami Premananda (1861 - 1918) (1)

- Swami Ramakrishnananda (1863 - 1911) (1)

- Swami Saradananda (1865 - 1927) (1)

- Swami Shivananda (1854 - 1934) (1)

- Swami Subodhananda (1867 - 1932) (1)

- Swami Trigunatitananda (1865 - 1914) (2)

- Swami Turiyananda (1863 - 1922) (3)

- Swami Vijnanananda (1868 - 1938) (1)

- Swami Vivekananda (2)

- Swami vivekananda - Swami Vivekananda — Soulful Tributes (1)

- Swami Vivekananda and Sri Ramakrishna (1)

- Swami vivekananda biography - Same Bible (1)

- Swami vivekananda biography - Tribute to Jesus Christ (1)

- Swami vivekananda book - Books on Holy Mother (1)

- Swami vivekananda book - Katha Upanishad (1)

- Swami vivekananda book - Sri Ramakrishna Institute of Paramedical Science (1)

- Swami vivekananda complete works - Inspiration for Meditation (1)

- Swami vivekananda photo - A Late-Night Search For The True Jesus - Connecticut Law Tribune (1)

- Swami vivekananda sayings - Sri Ramakrishna Sevaashrama (1)

- Swami Yogananda (1861 - 1899) (1)

- that Ramakrishna was God Incarnate (1)

- The complete works of swami vivekananda - Amritabindu Upanishad 3 (1)

- The complete works of swami vivekananda - Spiritual Teachers of India (1)

- the free encyclopedia (1)

- THE GOSPEL OF SRI RAMAKRISHNA (1)

- Too (1)

- Village girls carrying so many pots of water on their heads (1)

- Vivekananda biography - Overcoming Difficulties oMeditation (1)

- Vivekananda books - Staging an emphatic beginning - Times of India (1)

- Vivekananda kendra - You (1)

- Vivekananda ramakrishna Fear of Death (1)

- Vivekananda sayings - Sri Ramakrishna’s first experience of divine joy (ecstasy) (1)

- Vivekananda speech - Vivekananda Jayanti celebrations from tomorrow - Times of India (1)

- Vivekananda vedanta society - If You Want to Know India (1)

- Vivekananda’s Maha-Samadhi (1)

- Why Ramakrishna Matters (1)

- Words of Sri Ramakrishna (1)

- Yoga and Weight Training - Never the Twain Shall Meet? - (1)

2009 Slideshows

Recent Comments

Followers

Healing Through Faith and Love - A Case Study of Sri Ramakrishna

Patron Deity of Bengali Theatre |

It is a little known fact that actors in Bengali theatre, prior to entering the stage, bow down before the image of an unshaved, rustic-looking, middle-aged man, who is now unofficially the patron deity of all dramatic performance in the region. It becomes all the more intriguing when we realize that the gentleman in question was an unlettered individual who was never formally related to theatre and saw only a few plays during his own lifetime.

The story of how this came to be about begins on February 28, 1844, with the birth of a boy named Girish at Calcutta. Girish lost his mother when he was eleven and his father at fourteen. From his boyhood, he was a voracious reader but left school since he found the formal atmosphere detrimental to the process of learning. Without the restraining hand of a loving guardian, Girish's life drifted into drunkenness, debauchery, waywardness and obstinacy. He had to earn his living through a succession of office jobs, which he found thoroughly boring. His spare time was devoted to the theatre, both as playwright and performer. He was, in fact, a bohemian artist. An early marriage proved unable to stabilize his lifestyle and his wife passed away when he was thirty. Thus did he lose his mother in childhood, father in boyhood and wife in early manhood.

For the next fifteen years he worked in various capacities in different offices. He continued to indulge his appetites but also remained devoted to writing and acting. In his late thirties, he had already begun to be recognized as the father of modern Bengali drama. He was single-handedly revitalizing the revival of theatre by producing a vast body of dramatic work in the Bengali language, and at the same time was molding the first generation of actors and actresses by leading from the front; in fact, such was his versatility that he often played two or three roles in the same play. In 1883, the Star Theatre was opened in Calcutta with his money; this later developed into an active center for the evolution of Bengali drama.

Girish Chandra Ghosh (1844-1912) |

In Girish's case, talent and licentiousness gradually achieved a state of peaceful co-existence. He himself sized up his personality as follows: 'from my early boyhood I was molded in a different way. I never learned to walk a straight path. I always preferred a crooked way. From childhood it had been my nature to do the very thing I was forbidden to do.'

Kali Temple of Dakshineswar |

Skepticism

The course of Girish's tumultuous life continued till he read one day about a holy personality who was living in the famous shrine of Goddess Kali (Dakshineshwar) near Calcutta.

Sri Ramakrishna in Ecstasy |

A skeptical Girish, without ever having met the sage, concluded that he was probably a fake. However, soon after he heard that the guru would be visiting his neighborhood and decided to see him firsthand. It was nearing sunset when Girish reached the place, and lamps were being brought into the room. Yet the ascetic kept asking, "Is it evening?" This confirmed Girish's earlier opinion, 'what pretentious play-acting, it is dusk, lights are burning in front of him, yet he cannot tell whether it is evening or not' thus murmuring under his breath and not recognizing the saint's super conscious stage, he left the premises. Thus was the first impression of Girish Chandra Ghosh, the father of modern Bengali theatre, regarding Sri Ramakrishna, the beloved saint and priest of one of India's most renowned Kali temples.

Some years later, Girish saw the holy man again, at the house of a common acquaintance. In his own words: 'after reaching there, I found that the sage had already arrived and a dancing girl was seated by his side and singing devotional hymns. Quite a large gathering had assembled in the room. Suddenly my eyes were opened to a new vision by the holy man's conduct. I used to think that those who consider themselves param-yogis or gurus do not speak with anybody. They do not salute anybody. If strongly urged they allow others to serve them. But his behavior was quite different. With the utmost humility he was showing respect to everybody by bowing his head on the ground. An old friend of mine, pointing at him, said sarcastically: "The dancing girl seems to have a previous intimacy with him. That's why he is laughing and joking with her." But I did not like these insinuations. Just then, another of my friends said, "I have had enough of this, let's go."' Girish went with him. He had half wanted to stay, but was too embarrassed to admit this, even to himself.

Lessons in Humility

Only a few days after this, on September 21, 1884, the saint and some of his devotees visited the Star Theatre, to see a play based on the life of the great Vaishnava devotee Shri Chaitanya, authored and directed by Girish. The latter reminisced: 'I was strolling in the outer compound of the theatre one day when a disciple of Sri Ramakrishna came up to me and said: "The guru has come to see the play. If you will allow him a free pass, well and good. Otherwise we will buy a ticket for him." I replied: "He will not have to purchase the ticket. But others will have to." Saying this, I proceeded to greet him. I found him alighting from the carriage and entering the compound of the theatre. I wanted to salute him, but before I could do so he saluted me. I returned his greeting. He saluted me again. I bowed my head and he did the same to me. I thought this might continue forever, so I let him perform the last salute (which I answered mentally) and led him upstairs to his seat in the box.'

This was Girish's third meeting with Ramakrishna; but his intellect continued to refuse to accept another human being as a guru. This is how he reasoned: 'after all, the guru is a man. The disciple also is a man. Why should one man stand before another with folded palms and follow him like a slave? But time after time in the presence of Sri Ramakrishna my pride crumbled into dust. Meeting me at the theatre, he had first saluted me. How could my pride remain in the presence of such a humble man? The memory of his humility created an indelible impression on my mind.'

Three days later, Girish was sitting on the porch of a friend's house when he saw Ramakrishna approaching along the street: 'No sooner had I turned my eyes towards him than he saluted me. I returned it. He continued on his way. For no accountable reason my heart felt drawn towards him by an invisible string. I felt a strong urge to follow him. Just then, a person brought to me a message from him and said: "Sri Ramakrishna is calling you." I went. He was seated with a number of devotees around him. As soon as I sat down I asked the following question:

"What is a guru?"

"A guru is like the matchmaker who arranges for the union of the bride with his bridegroom. Likewise a guru prepares for the meeting of the individual soul with his beloved, the Divine Spirit." Actually, Sri Ramakrishna did not use the word matchmaker, but a slang expression, which left a more forceful impression. Then he said: "You need not worry, your guru has already been chosen."

Girish, however, was a complex personality: a mixture of shyness, aggression, humility and arrogance. Although in one corner of his heart he did believe that Ramakrishna was the guru who he had hoped for, another part of his old self revolted against the idea. On December 14th of the same year, the playwright was in his dressing room when a devotee came up to inform him of Ramakrishna's arrival. "All right," Girish said rather haughtily, "take him to the box and give him a seat."

"But won't you come and receive him personally?" The devotee asked.

"What does he need me for? " said the annoyed Girish. Nevertheless, he followed the disciple downstairs. At the sight of Ramakrishna's peaceful countenance Girish's mood changed. He not only escorted the saint upstairs but also bowed down before him and touched his feet. Later Girish said: 'seeing his serene and radiant face, my stony heart melted. I rebuked myself in shame, and that guilt still haunts my memory. To think that I had refused to greet this sweet and gentle soul! Then I conducted him upstairs. There I saluted him touching his feet. Even now I do not understand the reason, but at that moment a radical change came over me and I was a different man.'

Closeup of Ramakrishna's face in Samadhi cropped from a photograph taken on 21 September 1879 |

The Transforming Power of Faith

'Soon he started conversing with me. He spoke of several things while I listened longingly. I felt a spiritual current passing, as it were, through my body from foot to head and head to foot. All of a sudden Sri Ramakrishna lost outer consciousness and went into ecstasy, and in that mood he started talking with a young devotee. Many years earlier I had heard some slandering remarks against him, made by a very wicked man. I remembered those words, and at that moment his ecstasy broke and his mood changed. Pointing towards me, he said, "There is some crookedness in your heart." I thought, 'Yes indeed. Plenty of it - of various kinds." But I was at loss to understand which kind he was particularly referring to. I asked, "How shall I get rid of it?" "Have faith," Shri Ramakrishna replied.

On another occasion when Ramakrishna offered Girish a spiritual discourse, the latter stopped him short saying: "I won't listen to any advice. I have written cartloads of it myself. It doesn't help. Do something that will transform my life." Girish had a writer's skepticism about the authority of the written word. Ramakrishna was highly pleased to hear his view and asked a disciple to sing a particular song whose words went like this: "Go into solitude and shut yourself in a cave. Peace is not there. Peace is where faith is, for faith is the root of all." At that moment Girish felt himself cleansed of all impurities and doubts: 'my arrogant head bowed low at his feet. In him I had found my sanctuary and all my fear was gone.'

Girish's faith however required constant strengthening; years of suffering and torment had damaged it severely. In a later meeting he again directed the question to Ramakrishna:

"Will the crookedness of my heart go?"

"Yes it will go."

Girish repeated the question and received the same reply. The process was replayed twice until one of the other disciples reprimanded Girish: "Enough. He has already answered you. Why do you bother him again?" The theatre veteran turned towards the devotee to rebuke him since no one who dared criticize him ever escaped the lash of his tongue. But he controlled himself thinking: 'my friend is right. He who does not believe when told once will not believe even if he is told a hundred times.'

Venerating with Poison

One night, while Girish was in a brothel with two of his friends, he felt a sudden desire to see Ramakrishna. Despite the lateness of the hour he and his friends hired a carriage to Dakshineshwar. They were very drunk and everyone was asleep. But when the three tipsily staggered into Ramakrishna's room, he received them joyfully. Going into ecstasy, he grasped both of Girish's hands and began to sing and dance with him. The dramatist thus described his feelings: 'here is a man whose love embraces all - even a wicked man like me, whose own family would condemn me in this state. Surely, this holy man, respected by the righteous, is also the savior of the fallen.'

Girish, however, was not always so pleasant when drunk. Once at the theatre he publicly abused Ramakrishna, using the coarsest and most brutal words. All those present were shocked and advised the sage to sever all links with the playwright.

It is interesting to read what Girish himself says about this incident:

'Although I had come to regard Sri Ramakrishna as my very own, the scars of past impressions were not so easily healed. One day, under the influence of liquor, I began to abuse him in most unutterable language. The devotees of the master grew furious and were about to punish me, but he restrained them. Abuse continued to flow from my lips in a torrent. Sri Ramakrishna kept quiet and silently returned to Dakshineshwar. There was no remorse in my heart. As a spoiled child may carelessly berate his father, so did I abuse him without any fear of punishment. Soon my behavior became common gossip, and I began to realize my mistake. But at the same time I had so much faith in his love, which I felt to be infinite, that I did not for a moment fear that Sri Ramakrishna could ever desert me.'

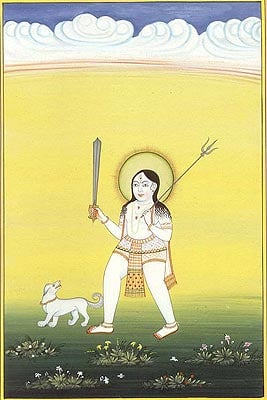

Subduing the Polluter of River Yamuna |

A common friend reminded Ramakrishna of the story of the serpent Kaliya, who, while battling Krishna, spewed enormous quantities of venom and said: "Lord you have given me only poison, where shall I get the nectar to worship you?" Similarly, Girish too had worshipped Ramakrishna with abuse, which was in accordance with his nature.

Ramakrishna smiled and immediately asked for a carriage to go to Girish's house, where he found the latter repentant. Seeing the guru, Girish was overwhelmed. He said, "Master if you had not come today, I would have concluded that you had not attained that supreme state of knowledge where praise and blame are equal, and that you could not be called a truly illumined soul." On another occasion Ramakrishna had told Girish: "You utter many abusive and vulgar words; but that doesn't matter. It's better for these things to come out. There are some people who fall ill on account of blood poisoning; the more the poisoned blood finds an outlet, the better it is for them. You too will be purer by the day. In fact, people will marvel at you."

Binding Through Freedom

One night, Girish drank himself into unconsciousness at the house of a prostitute. In the morning, he hastened to visit Ramakrishna. He was full of remorse but had not neglected to bring a bottle of wine with him in the carriage. On arriving at Dakshineshwar, he wept repentantly and embraced Ramakrishna's feet. Then, suddenly, he felt in urgent need of drink, and discovered, to his dismay, that the carriage had already driven off. But presently a smiling Ramakrishna produced not only the bottle, but Girish's shoes and scarf as well; he had privately asked a devotee to bring them from the carriage before it left. Girish could not control himself; he drank shamelessly before them all - and, having done so, was again remorseful. "Drink to your heart's content" Ramakrishna told him, "It won't be for much longer." Girish said later that this was the beginning his abstention from intoxicating drinks. But the abstention was gradual; and this was certainly not the last time that Girish was drunk in his guru's presence. Sri Ramakrishna never forbade Girish to drink because he knew that it takes time to change deep-rooted habits. Yet the silent influence of the guru's love worked wonders. In the playwright's own words: 'from my early childhood it had been my nature to do the very thing that I was forbidden to do. But Sri Ramakrishna was a unique teacher. Never for a moment did he restrict me, and that worked a miracle in my life. He literally accepted my sins and left my soul free. If any of his devotees would speak of sin and sinfulness, he would rebuke him saying, "Stop that. Why talk of sin? He who repeatedly says, 'I am a worm, I am a worm,' becomes a worm. He, who thinks, 'I am free,' becomes free. Always have that positive attitude that you are free, and no sin will cling to you."'

The Power of Attorney

One day Girish finally surrendered himself at the feet of Ramakrishna and asked him for instruction. "Do just what you are doing now," said the guru. "Hold on to god with one hand and to the material world with the other. Think of god once in the morning and once in the evening, no matter how much work you have pending." Girish agreed that this sounded simple enough. But he then reflected on his disorganized life, so much on the mercy of impulses and emergencies and realized that he did not even have fixed hours for eating and sleeping; how then could he promise to remember god? Making a false commitment was out of the question.

Ramakrishna, as if reading his mind said: "Very well, then remember god just before you eat or sleep. No matter what time of the day it is." Girish however, couldn't even make this simple promise, the fact being that any kind of self-discipline was repugnant to him. "In that case," said Ramakrishna, "give me your power of attorney. From this moment on, I'll take full responsibility for you. You won't have to do anything at all."

Girish was overjoyed. This is what he had been wanting all the time; to be rid of responsibility and guilt forever. He readily agreed to the suggestion and thought to himself, 'now will I be as free as air.' He was however mistaken - as he soon found out. By consenting, he had turned himself into Ramakrishna's slave. Whenever Girish indulged himself, he was forced to think of the tremendous moral burden he would be placing on his guru. In fact, he found it hard to not constantly think of Sri Ramakrishna before performing any action.

The Garlic Container

One day he went to a brothel intending to spend the night there. At midnight however, he experienced an unbearable burning sensation all over his body and had to immediately leave the place to return home. Girish was reminded of the time when Ramakrishna had compared him to a cup of garlic paste. Though such a container may be washed an umpteen number of times, it is not possible to get rid of the smell altogether. "Will my smell go?" Girish had enquired. "Yes it will. All offensive odor vanishes when the vessel is heated in a blazing fire." Was this the same heat that was tormenting him now? So wondered the playwright.

In later years he would tell young devotees that the way of complete self-surrender was actually much harder than the way of self-reliance and effort: "Look at me, I'm not even free to breathe, Sri Ramakrishna has taken full possession of my heart and bound it with his love."

The Guru as Mother (In Girish's Own Words)

'One day, when I arrived at Dakshineshwar, Sri Ramakrishna was just finishing his noonday meal. He offered me his dessert, but as I was about to eat it, he said: "Wait. Let me feed you myself." Then he put the pudding into my mouth with his own fingers, and I ate as hungrily and unself-consciously as a small baby. I forgot that I was an adult. I felt like a child whose mother was feeding him. But now when I remember how these lips of mine had touched many impure lips, and how my guru had fed me, touching them with his holy hand, I am overwhelmed with emotion and say to myself: "Did this actually happen? Or was it only a dream?" I heard from a fellow devotee that Sri Ramakrishna saw me as a little baby in a divine vision. And from then, whenever I was with him, I would actually feel like a child.'

Here it is also relevant to observe that though Girish had the company of his mother till the age of eleven, he only had a limited interaction with her. This restriction was due to an innate fear on the part of the parent that if she came near her children she would lose them; blaming herself for the many such bereavements she had already suffered before Girish.

The Vision of Bhairava

Long before he had met the dramatist, Sri Ramakrishna had a vision, which he described as follows: 'One day, when I was meditating in the Kali temple, I saw a naked boy skipping into the temple. He had a tuft of hair on the crown of his head, and was carrying a flask of wine under his left arm and a vessel of nectar in his right. "Who are you?" I asked. "I am Bhairava," he replied. On my asking the reason for his coming, he answered, "To do your work." Years later when Girish came to me I recognized that Bhairava in him.'

Bhairava |

In fact, Ramakrishna had often chided his disciples who derided Girish's enchantment with the bottle, saying, "What harm can alcohol possibly cause to someone who embodies Bhairava himself? None other than our beloved Mother Kali can ever judge or restrain him. We, who are her mere servants, may not even dare to do so. Girish is not a hypocrite, he is the same, inside and outside." The analogy with Bhairava is both apt and instructive. Bhairava was generated from the wrath of Shiva, when the latter was forced to listen to the vain boastings of another deity (Brahma). Having such provocative origins, holding within himself a simmering potential, Bhairava is thus visualized in Indian thought as an ambivalent, excitable and dangerous character, reflecting the emotions aroused at his birth, and even today is worshipped with offerings of alcohol in many shrines across India.

The bonding through sharing of food was further strengthened when one day Girish went to the house of a friend, who too was a devotee of Ramakrishna. He found the host cleaning rice. Now, the latter was a rich landlord with many servants, but nevertheless he was performing this unaccustomed job himself. Girish was amazed and enquired of the reason. The householder replied: " The master is coming today, and he will have his lunch here. So I am cleaning the rice myself."

Girish was touched by this extraordinary devotion. He reflected on his own ability to be of such service to Ramakrishna. He returned home and lay on the bed thinking, 'Indeed, god comes to the home of those who have devotion like my friend. I am a wretched drunkard. There is no one here who can receive the master in the proper manner and feed him.' Just then there was a knock on his door. Startled he jumped up. In front of him stood the master. "Girish I am hungry, could you give me something to eat?" There was no food in the house. Asking Sri Ramakrishna to wait, he rushed to a restaurant nearby and brought home some fried bread and potato curry. The food, coarse and hard, was much different from what the frail guru's constitution permitted. Nevertheless, he relished it with visible joy and delight.

A Unique Solution

The House where the Unwell Master was Taken |

As time progressed and age took over Ramakrishna, his health began to deteriorate. On the advise of doctors he was moved outside the city where the air was felt to be better.

An arrangement was made whereby the householder disciples contributed money for his treatment, food and rent. The younger, unmarried devotees, who later would establish the Ramakrishna Mission, managed the household, including the nursing and shopping. After a while however, some of the householders felt that the expenditure was getting out of hand and demanded that a strict accounting system be maintained. The youngsters felt offended and decided not to accept any more money from them. When the situation reached a flashpoint, Girish came forward with a solution. He simply set fire to the account book in front of everybody. Then he told the householders to each contribute according to his means and that he would make up the shortfall. To the unmarried monks he said: "Don't worry. I shall sell my house if the need arises and spend every bit of the money for the master." Whatever might have been the fate of Ramakrishna's physical well being, one thing was certain - Girish's healing was complete - and he later remarked in humor: 'Had I known that there was such a huge pit in which to throw one's sins, I would have committed many more.' It was this transformed soul who began the practice of paying homage to Sri Ramakrishna before the commencement of a theatrical performance.

References and Further Reading

- Blurton, T. Richard. Hindu Art: London, 1992.

- Chetanananda, Swami. Ramakrishna As We Saw Him: Calcutta, 1999.

- Chetanananda, Swami. They Lived with God (Life Stories of Some Devotees of Sri Ramakrishna): Kolkata, 2002.

- Isherwood, Christopher. Ramakrishna and His Disciples: Kolkata, 2001.

- M. The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna (Tr. into English by Swami Nikhilananda): Madras, 1996.

- M. The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna 2 vols. (Tr. into Hindi by Suryakant Tripathi Nirala): Nagpur, 2004.

- Mishra, Krishanbihari. Ramakrishna Paramhamsa Kalpatru ki Utsav Lila (Hindi): New Delhi, 2004.

- Muller, F. Max. Ramakrishna His Life and Sayings: Kolkata, 2005.

- Ramakrishna Sri. Sayings of: Madras, 2004.

- Ramakrishna Sri. Tales and Parables of: Chennai, 2004.

- Rolland, Romain. The Life of Ramakrishna: Kolkata, 2003.

- Saradananda, Swami. Sri Ramakrishna and His Divine Play (Tr. by Swami Chetanananda): St. Louis, 2003.

0 comments:

Post a Comment